Most Americans shy away from Latin or Greek sounding words and one at the top of the list to find out about is Habeas Corpus. In Latin, Habeas Corpus means that “you should have the body” or “produce the body.” But in our legal system, Habeas Corpus means that anyone arrested cannot be held indefinitely without a judge reviewing the government’s proof. When Habeas Corpus is “suspended,” it suspends a court’s power to force the government to make a showing of why an arrest is justified.

It works like this: Once the government “suspends” Habeas Corpus, anyone arrested is kept in jail until a government official decides to either file a case, file a charge, or allow the detainee any access to an impartial hearing in court. It is one of those fundamental constitutional rights that are the underpinning of due process, equal protection and fundamental fairness. It gives individuals the right and the power to have a court review any arrest and decide if there is sufficient evidence to bind that person over for a trial.

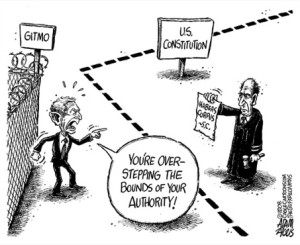

It exists as a fundamental and very elemental writ and once filed, the arresting agency (Federal or State) must immediately “produce the body” (Habeas Corpus) before a judge who will ask the government why that person is in jail and when and what charges the prosecutor believes he/she can sustain. Without access to a court and a fair and impartial hearing, anyone arrested remains in custody for…well maybe for weeks, months, or (as we see in the Guantanamo detainees) years.

Historically, Habeas Corpus was first inspired as a fundamental right in the Magna Carta in 1215, the “Great Charter” issued at Runnymede on the banks of the Thames River. The Magna Carta was an official document issued by the British King John after a revolt by the British nobility in which British kings guaranteed they would respect feudal rights and privileges, uphold the nation’s laws, and uphold the freedom of the church. In the U.S., the right of Habeas Corpus was inserted in the Article 1, Section 9 of the U.S. Constitution and only during the early years of the American Civil War was Habeas Corpus suspended. The reason was that Maryland was about to join the Confederacy and Washington D.C., the nations capital, was so full of spies and agents for the Confederacy that Abraham Lincoln asked the U.S. Congress to suspend Habeas Corpus so they could deal with what was a real emergency.

What is pending today is the real possibility that ISIS (ISIL) may commit some atrocity on U.S. soil, similar to the murderous attack that killed 129 people in Paris. At that moment it is very likely that the Federal government will ask the Congress to act (as the constitution permits) to suspend Habeas Corpus for the duration of an emergency. Suspension of Habeas Corpus is an easy governmental response to a terrorist event. We are seeing something very similar in France as it has declared a state of emergency and authorized the police to investigate, arrest and detain suspects and then, at a pace and time convenient to the French government, begin the process of proving guilt. The French do not have a formal process in its criminal laws, but we do, and that is the writ of Habeas Corpus. As time goes forward the subject of Habeas Corpus is something we can all expect to be very topical and current.

If terrorists commit an atrocity on U.S. soil and the federal government wants to act expeditiously to arrest and detain suspects and wants to be free of the responsibility to respond to an independent judiciary, you will hear our federal government ask to suspend Habeas Corpus. Without it, no one arrested has the ability to ask the government to simply make a showing of what proof it intends to use at a trial. It is only a burden if the government wants to act without controls or any obligation to prove up a charge. If we suspend Habeas Corpus, it is almost a certainty that police agencies will make large sweeping arrests without having to answer to a judge who will ask: “Why?”

South Florida Criminal Defense Lawyer Blog

South Florida Criminal Defense Lawyer Blog